GEORGE FREDERICK AUGUSTUS RUXTON’S OTHER RIFLE

Miles Gilbert

An article in the Autumn 2001 Double Gun Journal (as it was then known) mentioned double guns used by British sportsmen in the American West 1833-1883. Among those sportsmen listed George Ruxton was known to have had both a shotgun and a double rifle. His written accounts of travels in the Rocky Mountains during 1846-1847 published under the titles Adventures in Mexico and the Rocky Mountains and Life in the Far West Among the Indians and the Mountain Men made a most important contribution to our knowledge of the fur trade period. His word pictures filled with romance, danger, and the colorful, rustic dialogue of the beaver trappers has been utilized by many a western novelist and Hollywood script writer. Consider the Disney Studios ‘Saga of Andy Burnett’ or Frazier Heston’s The Mountain Men starring his father Charlton for example. Ruxton’s writing combined with the art of Alfred Jacob Miller, who accompanied Sir William Drummond Stewart to a mountain man rendezvous in 1837 provide a charming look at that life and time.

George Frederick Augustus Ruxton was born to Anna Maria Hay Ruxton and John Ruxton, Esquire at Tonbridge, Kent on July 24, 1821. His maternal grandfather was Colonel Patrick Hay, a descendent of the House of Tweeddales. Ruxton attended Turnbridge School and began his education at Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, but being something of a rebel he left before getting his commission. “I was a vagabond in all my propensities. Everything quiet or commonplace I detested and my spirit chafed within me to see the world and participate in scenes of novelty and danger.”

He was a soldier during the Spanish Civil War 1833-1839. He became a lancer under Diego De Leon and received the Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand from Queen Isabella II for his gallantry at Belascoain. Then he served as an ensign in Princess Victoria’s 89th Regiment of Foot, also known as the Royal Irish Fusiliers, in Canada. Having become intrigued by the lives of Native Americans and trappers in 1843 he sold his Lieutenant’s commission in the British Army and became a hunter with the Ojibwa in Upper Canada. After returning to England he set sail from Liverpool in the spring of 1844 to explore central Africa, but lack of support from the British government stopped that enterprise before he wanted. He did manage to study African bushmen and presented a paper on them to the Ethnological Society of London on November 26, 1845.

The United States went to war with Mexico in May 1844 over the border of Texas. Ruxton secured an appointment as a British commercial attache’ charged with protecting the lives and property of British citizens in Mexico. Nowadays he would have been identified by the US as a spook at least or as a spy at worst. In July he made his way from Vera Cruz to Mexico City and thence north into New Mexico where he encountered Lt James Abert of the US Corps of Topographical Engineers. He was very favorably impressed with the West Point graduates he met but equally unimpressed with the New Mexico Volunteers. He was particularly disgusted with their lack of discipline and was not surprised that such lack resulted in the loss of 800 sheep and the lives of two volunteers as accomplished by only three Navajo raiders.

Before we have a look at the rifle itself a few paragraphs of classic Ruxton are in order to set the stage and give a context for its use: “Apart from the feeling of loneliness which any one in my situation must naturally have experienced, surrounded by stupendous works of nature, which in all their solitary grandeur frowned upon me, and sinking into utter insignificance the miserable mortal who crept beneath their shadow; still there was something inexpressibly exhilarating in the sensation of positive freedom from all worldly care…that no more dread of scalping Indians entered my mind than if I had been sitting in Broadway in one of the windows of the Astor House….By the way, I may here remark that my sporting feelings underwent a great change when I was necessitated to follow and kill game for the support of life, and as a means of subsistence; and the slaughter of deer and buffalo no longer became sport when the object was to fill the larder…and although ranking under the head of the most red-hot of sportsmen I can safely acquit myself of ever want only destroying a deer or buffalo unless I was in need of meat….Although liable to an accusation of barbarism, I must confess that the very happiest moments of my life have been spent in the wilderness of the Far West and I never recall but with pleasure the remembrance of my solitary camp in the Bayou Salado, with no friend near me more faithful than my rifle, and no companions more sociable than my good horse and mules, or the attendant coyote which nightly serenaded us….Scarcely however did I ever wish to change such hours of freedom for all the luxuries of civilized life and unnatural and extraordinary as it may appear, yet such is the fascination of the life of the mountain hunter that I believe not one instance could be adduced of even the most polished of civilized men who once had tasted the sweets of its attendant liberty and freedom from every worldly care not regretting the moment he exchanged it for the monotonous life of the settlements nor sighing and sighing again once more to partake of its pleasures and allurements.”

“Nothing can be more social and cheering than the welcome blaze of the camp fire on a cold winter’s night, and nothing more amusing or entertaining, if not instructive, than the rough conversation of the single-minded mountaineers, whose simple daily talk is all of exciting adventure, since their whole existence is spent in scenes of peril and privation; and consequently the narration of their every-day life is a tale of thrilling accidents and hair-breadth escapes which, though simple matter of fact to them appear a startling romance to those who are not acquainted with the nature of the lives led by these men who with the sky for a roof and their rifles to supply them with food and clothing, call no man lord or master and are as free as the game they follow.”

“A hunter’s camp in the Rocky Mountains is quite a picture. He does not always take the trouble to build any shelter unless it is the snow season, when a couple of deer skins stretched over a willow frame shelter him from the storm. At other seasons he is content with a mere break wind. Near at hand are two upright poles, with another supported on the top of these, on which is displayed out of the reach of hungry wolf or coyote meat of every variety the mountains afford. Buffalo depouyilles (entrails, ed. note), hams of deer and mountain-sheep, beaver tails &c., stock the larder. Under the shelter of the skins hang his powder-horn and bullet-pouch; while his rifle, carefully defended from the damp, is always within reach of his arm. Round the blazing fire the hunters congregate at night, and whilst cleaning their rifles, making or mending moccasins, or running bullets, spin long yarns of their hunting exploits, &c.”

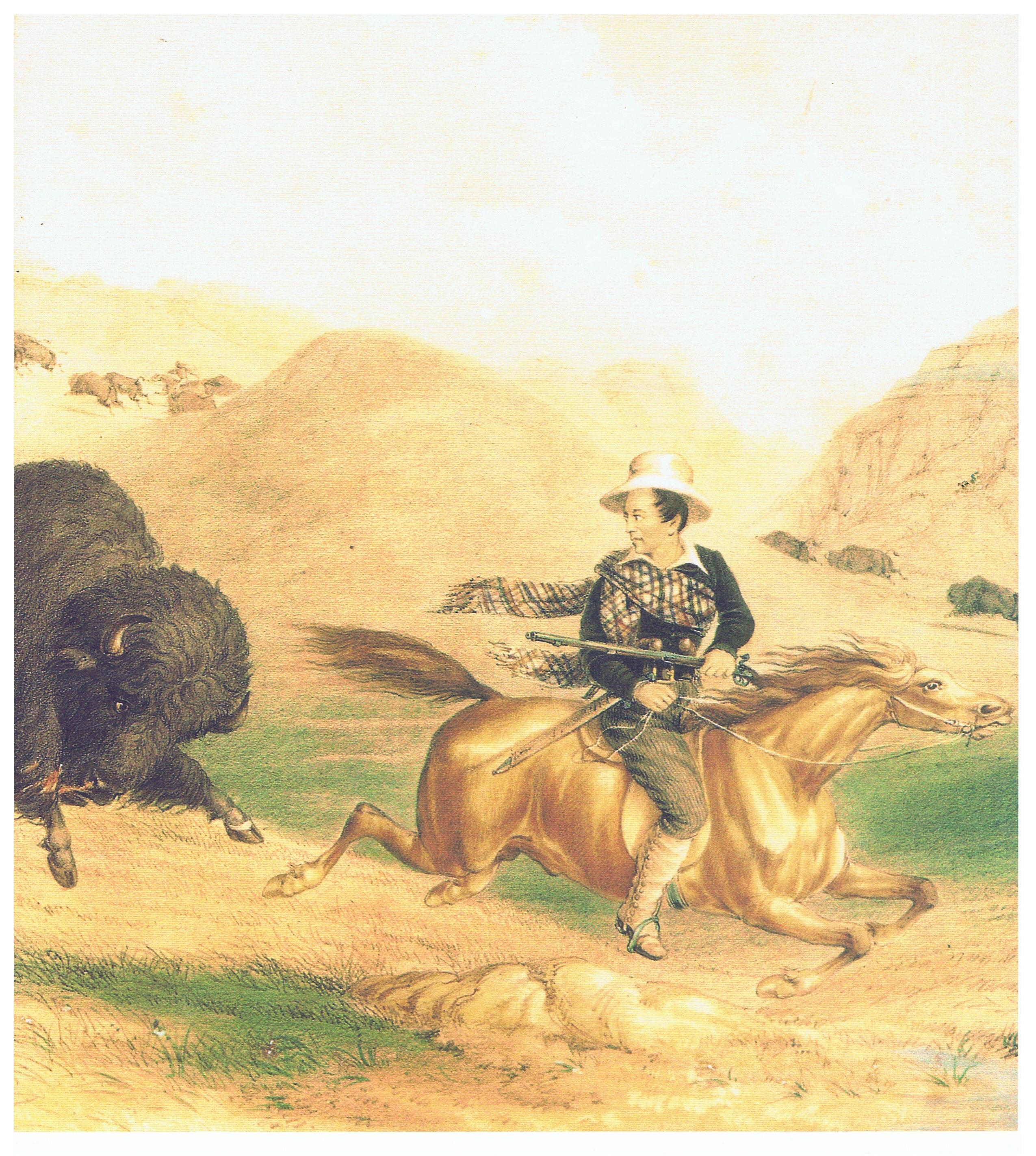

One of many of Ruxton’s own adventures in which his rifle played a significant part was in the turning of a buffalo stampede. One night in May 1847 he and his traveling companions, “…advancing toward the buffalo which were coming straight upon us, by shouting and continued firing of guns we succeeded in turning them.” The rifle presented here is typical in many respects to those produced for British hunters in the percussion period. It is 57 inches overall with a 40” barrel of .575 caliber, being as Ruxton said, of 25 to the pound. The straight octagon barrel is 1 1/8” across the flats and contributes to most of the 10 pound weight. The percussion bar action lock by Thomas K. Baker is equipped with a sliding safety behind the hammer. As a personal touch the right side of the stock bears his name in a lovely silver banner while on the cheek piece a silver escutcheon shows a very Catlinesque buffalo.

Departing from the British norm which many of us find to be perfection itself, Ruxton fell prey to the norm in the Far West and had his rifle’s shotgun butt replaced with a crescent butt in steel to match the other furniture. It seems that not a few British travelers were fascinated by them. An officer of Her Majesty’s navy observed one of Fremont’s scouts with such a rifle while he was in California during the Mexican War. Ruxton wrote that the Hawken rifle was a favorite of his peers in the mountains and he may very well have seen one in the Hawken shop in St. Louis. Perhaps because rifles used by the mountain men he traveled among had such crescent butts and he wanted to fit in he had his rifle modified while back in England prior to his return for his trip in 1848. While a crescent butt may give better purchase while wearing a heavy coat it is not nearly so comfortable as a shotgun butt when firing a heavy charge.

Alas for Ruxton, he had only just gotten back as far as St. Louis when he died on August 29, 1848. Cholera is suspected. His brother came down from Canada to gather his belongings. Almost forty years ago a regional Christie’s antique gun auction in Scotland included the Ruxton rifle and it was eventually obtained by Jim Gordon of Santa Fe. It is a featured part of the fur trade room along with a dozen Hawken and many other St. Louis made rifles in Jim’s Casa Escuela Museum located just off I-25 at the Glorieta, New Mexico exit. Call him for an appointment at (505) 982-9667. You will be treated to an amazing, magnificent collection of historic items ranging from the Spanish Entrada of 1540 right through the early ranching period. Jim is well known as the author of a multi-volume work on the Winchester 1873, a volume on knives of the early west, and a volume on firearms of the early west.

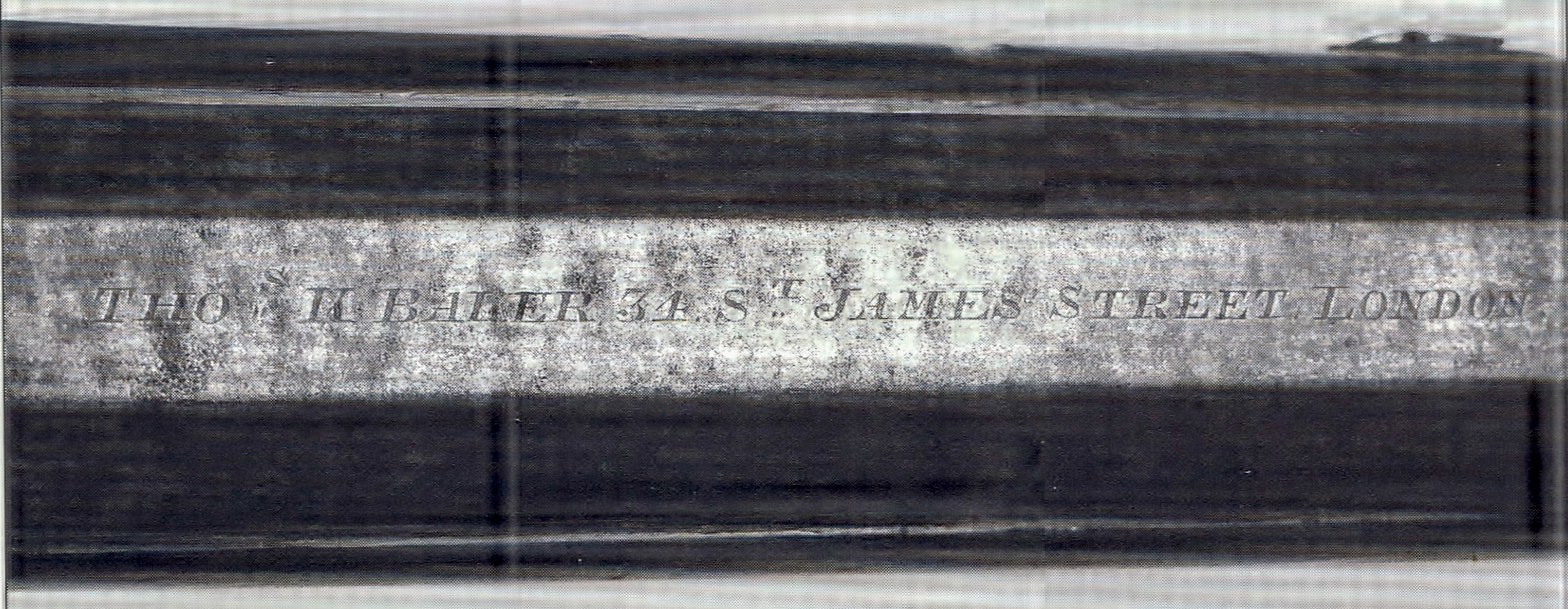

After 166 years the address of Thomas K. Baker’s business at 34 St. James Street, London is yet visible. According to Blackmore, Baker was active from about 1833 until after 1852. He relocated from 2 Bury Street, St. James’ to 34 St. James’ in 1846, so Ruxton may have had the rifle made for his 1846 trip. The single set trigger and safety still function. In addition to the butt plate modification, the rear sight may also have been changed. Rather than a typical wide v that one might expect there is a rather Germanic looking two leaf rear. The straight hand stock wears an iron pistol grip trigger guard. The long, heavy barrel is held in place by a hooked breech and two fore end wedges or keys, a’ la’ a proper St. Louis plains rifle.

The influence of George Catlin is easily seen in the buffalo on the decorative silver plate that Ruxton had on the cheek piece. Note that it crosses the wood added to accommodate the crescent butt.

Acknowledgments: Jim Gordon for access to the Ruxton rifle. Black and white photos from James Hanson’s article on Ruxton in the Museum of the Fur Trade Quarterly Vol 41, No. 2, 2005. The Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody. The National Cowboy Hall of Fame, Tulsa. Daughter and computer whiz Amanda Lane for technical assistance.

References Cited: Howard L. Blackmore, Gunmakers of London Supplement 1350-1850. Alexandria Bay, NY: Museum Restoration Services, 1999. George F. Ruxton, Life in the Far West Among the Indians and the Mountain Men, 1846-47. Rio Grande Press, Glorieta, NM 1972.